By Kali Koba

MTSC Editor’s Introduction

The facilitation team recently decided to open our website to publishing guest essays on a case by case basis. We are excited to publish “The Marks of Capital” by Kali Koba as our first guest essay. We have chosen to republish this text because we believe it effectively communicates the absurdities of pragmatism and ignorance that have plagued the US communist movement for over 150 years. The original article can be found here. All alterations have been made with the author’s consent. Of course, Kali’s and our views outside of this essay should not be misconstrued. Linking their substack is not an endorsement of everything they have written and their permission to republish is not an endorsement of every one of our writings.

The Marks of Capital

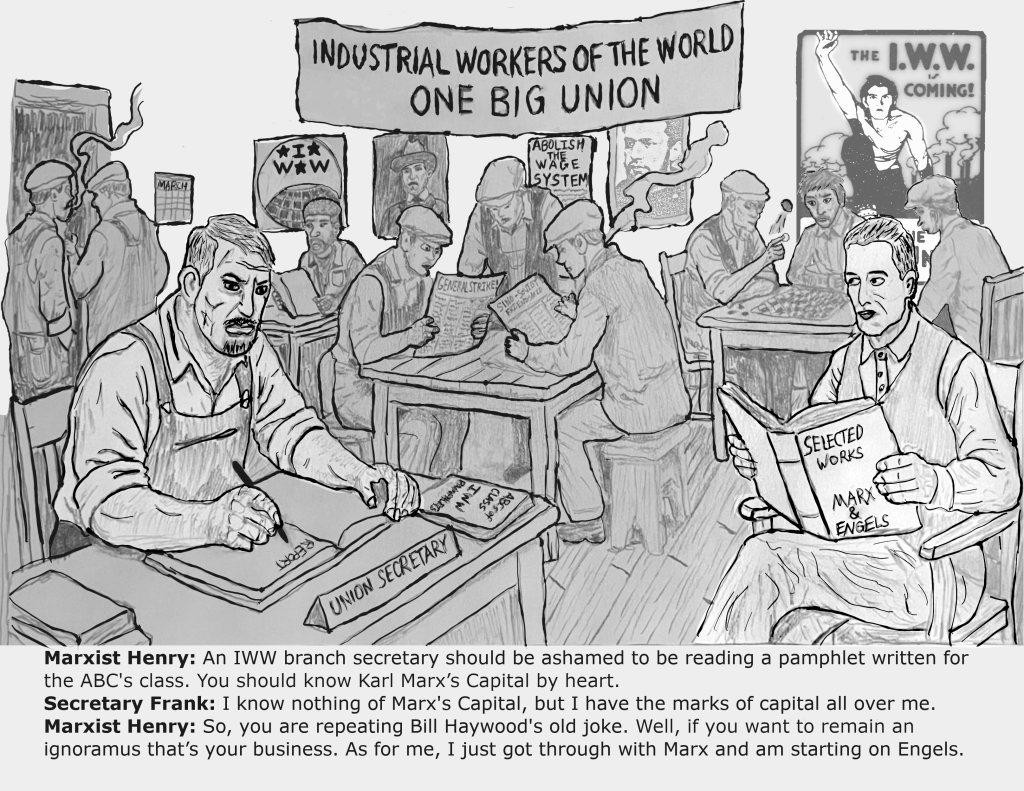

I’ve never read Marx’s Capital, but I have the marks of capital all over me.

— Bill Haywood1

If you have spent any prolonged period of time in Leftist spaces, you have heard this quote, or you have at least seen this sentiment repeated: lived experience is a valid substitute for theory. In fact, to many, it is superior. Reading theory is for those unlucky fools who weren’t gifted the knowledge-generating experience of pain and suffering. The reader of theory may frequently be asked to defer to the lived experiences of certain individuals or groups, but lived experience will never be asked to defer to theory. What preachers of this gospel fail to realize is that the role of theory is precisely to challenge lived experience; to expose, upend, and invert it.

While direct lived experience can be a source of knowledge, it is just as often a source of misunderstanding. In lived experience, the Sun seems to rise, fly overhead, and fall. Nearly all celestial bodies appear to cross the sky before disappearing, and they reappear only to repeat the cycle. In contrast, the Earth does not seem to move. From our point of view, the Earth seems stable. It does not rotate under our feet, and until rather recently we had no way of observing the planet from afar. If we stick strictly to the realm of our senses, it would appear that the entire universe revolves around a stationary Earth. The prevalence of geocentric models in the ancient world can be explained by this fact. Greek, Egyptian, and Islamic thinkers were not idiots. In many ways, they were at the forefront of human knowledge. Ptolemy was one of the most intelligent and accomplished astronomers on the planet when he proposed his model. How could they all have gotten it so wrong? They were misled by experience. The geocentric model seemed practically self-evident, and any criticism of it had to deal with that fact.

The transition to a heliocentric model of our solar system (and a model of the universe without a center) was initiated by a series of mathematical models, most notably those of Copernicus and Kepler, which proposed alternative explanations to fit the phenomena being observed. This scientific revolution did not emerge from direct experience but from rational attempts to account for direct experience. No one doubted that the universe might appear geocentric. What they doubted was that it really was. They instead sought to create a model that both accounted for the movements of celestial bodies and for the ways that they appeared in observation. Soon after, the invention of the telescope allowed Galileo to add entirely new data to the debates, data that seemed difficult to square with the old geocentric models. First gradually, then all at once, the geocentric model came tumbling down.

Scientific progress almost always takes this path. Lived experience furnishes us with models that seem to fit the facts, but deeper investigation and logical consideration lead us instead to understand things as being quite the opposite of what they appear to be. Thus, those who deny the theory of the evolution of the human species are fond of reminding us that we humans were not there to observe it. True science is not simply an account of what we can see. It is an account of why we see it that way, of the inner workings which result in these forms of appearance. This is as true in the social sciences as it is in astronomy or biology. Social systems, capitalism included, often appear to us as the precise opposite of what they are.

Marx himself draws this analogy when he tells us that, “a scientific analysis of competition is possible only if we can grasp the inner nature of capital, just as the apparent motions of the heavenly bodies are intelligible only to someone who is acquainted with their real motions, which are not perceptible to the senses.”2 In truth, this exposition of the real motions and an account of there necessary forms of appearance is basically the entire point of “Capital“. Marx’s project is exactly the kind of scientific revolution initiated by Copernicus. Lived experience is not a substitute for Marx’s work precisely because Marx’s work is an antidote to all the foppery and illusions of lived experience.

As the reader will have recognized in dismay, the analysis of the real, inner connections of the capitalist production process is a very intricate thing and a work of great detail; it is one of the tasks of science to reduce the visible and merely apparent movement to the actual inner movement. Accordingly, it will be completely self-evident that, in the heads of the agents of capitalist production and circulation, ideas must necessarily form about the laws of production that diverge completely from these laws and are merely the expression in consciousness of the apparent movement.3

We could bring out a great number of examples from Marx’s work, but for the sake of brevity and clarity, let us stick to one: the form of wages.

In “Capital,” Marx demonstrates that profit is gained by the capitalist on the basis that workers are paid for their labor power (their capacity for work) and yet provide their labor (their actual work). Without this understanding, the generation of profit remains a mystery, and it appears to spring from nowhere in particular, as if by magic. Previous writers had assumed that it was labor that was purchased by the capitalist, not labor power. If both labor and the means of production, the components of the production process, were purchased at their appropriate price, then where could the additional value present at the end of the week, taken as profit by the capitalist, be coming from?4 Capital appears to be self-expanding. This quasi-supernatural quality of capital to valorize itself was in fact the position held by many political economists before Marx. Even a thinker as powerful as Smith, who argues in favor of a labor theory of value in the early sections of his “Wealth of Nations,” is forced to abandon all reason and declare profit to emerge spontaneously from capital itself when faced with the real production process. Why was no one before Marx able to comprehend that the capitalist purchases labor power and reaps a profit off the difference between that price and the value of the labor provided? Because it appears to all involved that what the capitalist really buys is the labor itself.

This is easier to understand if we contrast wage labor with another historical form of exploitation. Under a corvée system, tenant farmers were forced to perform labor for a certain amount of time (say, for example, 40 days out of the year) on their lord’s land. It was apparent to all involved which portions of the year were worked for the farmers’ own benefit and which were worked for the lord. The period of exploitation was marked out explicitly both in time (the legally required 40 days) and space (the land being cultivated for the lord as opposed to the land cultivated for the farmer). In capitalism, things are quite different. Wages are paid either before the completion of the labor process (as an advance) or after. They thus appear as a compensation for the entire period of labor, rather than as a compensation for only the labor time necessary to reproduce their labor power. While the law set out a specific period of time for corvée labor to be performed, the period where the worker is reproducing their own means of subsistence and the period in which they are producing profit for the capitalist are not clearly distinguished. Similarly, since the laborer uses the same means and conditions of production to reproduce both themselves and the capitalist, there is no distinction in space. The corvée who had to plow a separate plot of land for the lord knew exactly who was benefiting from that labor. The wage laborer works the exact same plot of land (either literally in capitalist agriculture or metaphorically in the factory and so on) during both necessary and surplus labor time. The appearance of the wage obscures the entire relation of exploitation that underlies it. To the average observer, it seems as if the capitalist purchases labor, not labor power, and it seems as if the laborer is fairly compensated, not exploited. In lived experience, wages appear to represent the value or price of labor, which is exactly the opposite of what they actually represent: labor power.

As Marx put it:

We may therefore understand the decisive importance of the transformation of the value and price of labour-power into the form of wages, or into the value and price of labour itself. All the notions of justice held by both the worker and the capitalist, all the mystifications of the capitalist mode of production, all capitalism’s illusions about freedom, all the apologetic tricks of vulgar economists, have as their basis the form of appearance discussed above, which makes the actual relation invisible, and indeed presents to the eye the precise opposite of that relation.5

It is important to emphasize that it is both “the worker and the capitalist” who fall victim to the illusions generated by the wage form. Within the organized labor movement, past and present, it is impossible to escape phrases like, ‘an honest day’s pay for an honest day’s work.‘ Even these more politically conscious workers are under the impression that pay is granted for ‘a day’s work,’ i.e. for labor itself. They fail to realize the terms on which they are actually being exploited. But who am I to challenge their lived experience?

There are other problematic elements to these “lived experience” epistemologies, though I only feel compelled to touch on them briefly. Firstly, they presume that being victimized makes you better, smarter, and more coherent. As if our minds become clearer while being beaten. Unfortunately, traumatic experiences are generally terrible for the thinking subject. They more often serve to leverage people away from reality than to bring them back towards it. In fact, solipsism and narcissism (in the clinical and not moral sense) is a common response to trauma, which may go some way to explaining why so many feel the need to claim their “unique” suffering as the ultimate and unsurpassable basis for “good” politics. There is also something of the abuser in all this: ‘The pain I inflict will teach you a valuable lesson.‘ Still more, something of the torturer: ‘We’ll get the truth out of you one way or another.’ Bill Haywood said he has the “marks of capital” rather than the “Capital” of Marx, but that’s objectively worse and less instructive.

Secondly, a lot of the “theory” people refuse to read is actually just accounts of the experiences of others. What is history except the “lived experience” of past generations? What is philosophy except the “lived experience” of a philosophical thinker? What people are really saying when they refuse to engage with theory in favor of their own lived experience is that they they value their own lived experience over the lived experiences of others. Once again, we’re back to narcissism.

Third, there is a neoclassical leaning to the whole idea that we should all defer political power to those who have suffered the most. When you hear these people speak, it’s hard not to feel like they are telling you just how hard they had to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. That is not to discount their suffering, which in many cases has been severe. It is only to say that many people suffer equally as badly and don’t come out the other side demanding everyone submit to their personal whims and crackpot theories. I don’t think growing up homeless justifies a billionaire’s exploitation of their workers, and I also don’t think it means you get to be a tyrant at your local food bank or DSA meeting. It doesn’t mean you don’t have to put in the work like the rest of us, and it definitely doesn’t mean you found the cheat code to instantly being the vanguard of the struggle for liberation. It just means something terrible happened to you. You can certainly learn from it, but it didn’t necessarily teach you anything.

All of these are, however, side points (though I’m sure they will cause the most fuss). The key argument to remember is this: Lived experience is equally a source of both truths and illusions. As Marx, perhaps the greatest mind in the history of the social sciences said, “all science would be superfluous if the form of appearance of things directly coincided with their essence.”6 As that is not the case, scientific investigation remains a necessity. And who better to start with than Marx?

- This quote is widely attributed to Bill Haywood but this has not been verified. A Libcom discussion post (found here) discusses a few promising origin stories and potential sources. The earliest reference to Haywood is in “The Stool Pigeon,” a 1924 play by Phil Engle (found here). The relevant section reads,

Secretary: “I know nothing of Marx’s Capital, but I have the marks of capital all over me.”

The Marxian: “So, you are repeating Bill Haywood’s old joke.”

The earliest variation of the saying identified in the Libcom discussion is from 1919 with no mention of Haywood. It can be found here. The quote is rendered as, “The workers may not have read the Capital of Marx but they sure do bear the marks of capital,” with no author nor attribution. ↩︎ - Capital, vol 1, ch 12, pg 433 (all quotes are from Penguin editions) ↩︎

- Capital, vol 3, ch 18, pg 428 ↩︎

- To illustrate this: If the means of production have a full value of $10, and the labor purchased through wages has a full value of $10, then the product of the production process can only have a value of $20. Yet, it is sold at a value of $30. What is the cause of this additional $10? What Marx shows is that the $10 spent on wages does not represent the full value of the labor supplied but merely represents the value of labor power. Before Marx, political economists had to resort to all kinds of magical thinking to explain how the $10 surplus could emerge, as something, from nothing. ↩︎

- Capital, vol 1, ch 19, pg 680 ↩︎

- Capital, vol 3, ch 48, pg 956 ↩︎